When Jean Renoir died: how the Los Angeles Times got an obituary from Orson Welles. Steve Wasserman tells the tale.

Friday, August 6th, 2021

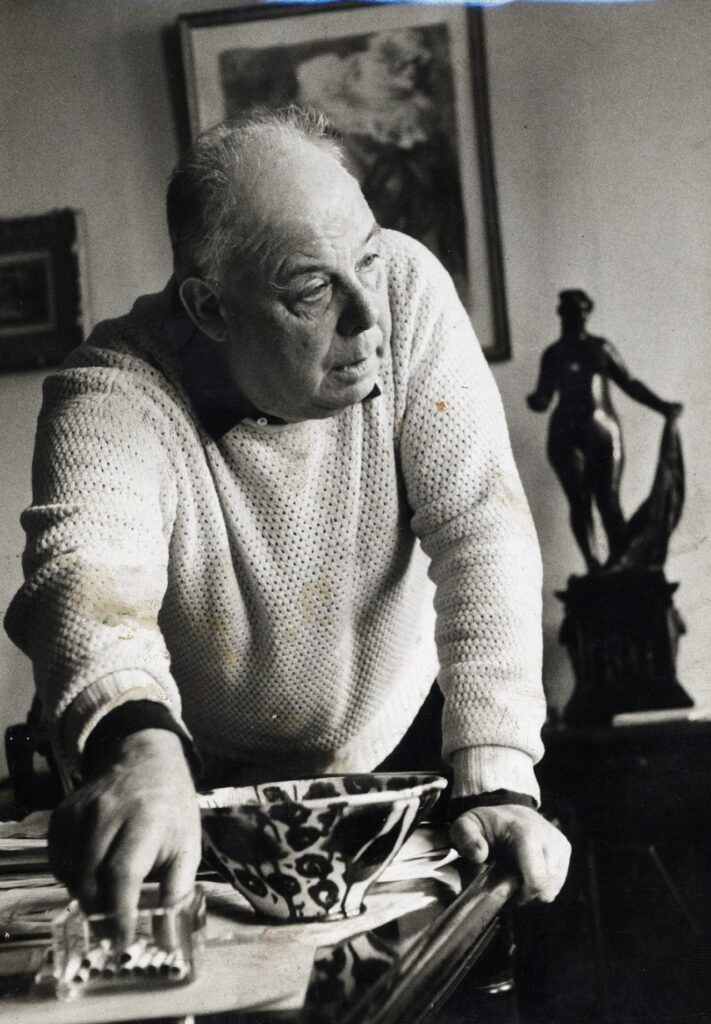

It’s a pleasure, always, to have a guest piece from my former Los Angeles Times Book Review editor … whoops! now he’s head of Heyday Books and my very own publisher … Steve Wasserman. Here’s what he wrote remembering the occasion of the 1979 death of the eminent film director, screenwriter, actor, producer and author Jean Renoir.

Here’s the story of how the Los Angeles Times finagled an obituary from Orson Welles.

My old friend Peter Biskind, Hollywood historian extraordinaire, has rescued from Henry Jaglom‘s jumbled closet the hours upon hours of table-talk Jaglom recorded during his years of lunches with Orson Welles. As I hoovered up these edited transcripts of the higher gossip, I thought fondly of my own encounter with Welles – an encounter that would lead to irregular meals (and something of a friendship) with the great man at his favored table at “Ma Maison.”

The story begins with the death of Jean Renoir in Beverly Hills in early 1979. I was then deputy editor of the Los Angeles Times Sunday Opinion section. The Times, in its infinite wisdom, had consigned news of Renoir’s demise to an AP wire story buried on page nineteen of the Sunday paper. I was beside myself with unhappiness. Here was one of the great directors of the twentieth century, dying in our backyard, as it were, banished to an ignominious squib on the paper’s inside pages instead of being ballyhooed prominently on the front page.

The honor of the paper was at stake, I felt. We needed to act immediately to commission a proper piece, honoring Renoir’s life and legacy, to publish in the next Sunday’s paper. Only Orson Welles, I felt, could do right by Renoir. But how to contact him? I knew only that Welles made a habit of eating lunch every Wednesday at “Ma Maison,” but I would need his piece, should he agree to write it, by Wednesday, or Thursday at latest, in order to make the Sunday paper. I remembered that Welles had some years before been the voice of the Paul Masson Winery, intoning “no wine before its time.” I called the winery and was referred to an ad agency in New York and was, in turn, given the name of Welles’s Manhattan agent. I rang and explained my purpose.

“So you want to reach Orson Welles, do you? Well, a lot of people want to reach him. Listen, kid, here’s what I’ll do. I’m gonna give you his office number. It’s a local number. Area code two-one-three. You’re unlikely to reach him, but if you do, will you do me a favor? Will you tell him to call his agent, for cryin’ out loud?”

I dialed the number. It rang and rang and rang. Finally, the receiver was slowly lifted off its cradle and what can only be described as an extraordinarily fey voice drawled hello. It was Welles’s assistant. I asked to speak to Welles. “I’m sorry, but Mr. Welles isn’t in.” “Do you expect him back soon?” “I do not know when he’ll be back. You see, Mr. Welles almost never comes in.” “Might I leave a message?” “Yes, if you must,” the voice said in tones of great exasperation. “But do understand that when Mr. Welles deigns to come into this office, he very often sees the stack of messages piled high on the desk and he sweeps them to the floor.”

The next morning, I got to work early. Already at my desk was my boss, Anthony Day, editor of the paper’s editorial pages. He was clutching my phone. “Yes, yes. I see him now, just coming in.” Cupping the receiver, he looked at me and stammered, “Steve, it’s. . .it’s Orson Welles. For you!”

I got on the horn and heard, in his inimitable voice, “Mr. Wasserman, this is Orson Welles. I did not know until I received your kind message that my great and good friend, Jean Renoir, had passed away. What, pray tell, would you have me do?”

I told him of the embarrassing and all but invisible notice that Renoir’s death had occasioned in the paper and that we had an obligation to do what we could to remove the stain of shame. Would he write a piece?

“How long? How about two-hundred-fifty words?” he offered. Given the length of Renoir’s life and his considerable achievement, I said a thousand might be better.

“Let’s split the difference and agree to five hundred.”

As for deadline. . .he boomed, “I know, I know: You needed it yesterday.”

“For you, Mr. Welles, the day after tomorrow would be fine.”

As for compensation … he cut me off: “Let us not sully art with talk of money. I count on you to do the right thing. You will do that, won’t you?”

I said I’d do my level best.

Wednesday came and went. No piece. We were keeping space open on the front page of the Opinion section. By noon on Thursday, we began to sweat. My phone rang. It was Gus, the paper’s receptionist-cum-security guard who manned the front desk in the paper’s art deco lobby, worthy of The Daily Planet, at the center of which slowly revolved a globe boasting national boundaries not redrawn since the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A man saying he was from Mr. Welles’s office was waiting for me.

I hurried down. And there, greeting me, was an apparition straight out of Sunset Boulevard. A man, kitted out in livery, replete with leather driving gloves, handed me a manila envelope, bearing Welles’s piece.

As I walked slowly up the stairs to my second-floor office, I read what Welles had written. It wasn’t five hundred words; it was nine pages, 2,000 words, typed double-spaced on an Underwood Five typewriter, and edited in Welles’ hand with a blue felt tip pen, the last page of which bore his signature. Every sentence had oxygen in it. The lede was unforgettable: “For the high and mighty of the movies a Renoir on the wall is the equivalent of a Rolls Royce in the garage. Nothing like the same status was accorded the other Renoir who lived in Hollywood and who died here last week.”

The essay was perfect, all about the uneasy intersection of art and commerce and, as I read it, I realized it was, of course, as much about Welles himself as it was about Renoir. It was about the trials and tribulations of neglected genius. It was, in a way, a kind of manifesto, a credo of artistic aspiration and principle.

The ending, too, was a doozy: “I have not spoken here of the man who I was proud to count as a friend. His friends were without number and we all loved him as Shakespeare was loved, ‘this side idolatry.’ Let’s give him the last word: ‘To the question “Is the cinema an art?” my answer is “What does it matter?. . .You can make films or you can cultivate a garden. Both have as much claim to being called an art as a poem by Verlaine or a painting by Delacroix. . .Art is ‘making.’ The art of love is the art of making love. . .My father never talked to me about art. He could not bear the word.'”

There was nothing to edit. Only to publish it as written. It was the last piece Welles ever wrote. It appeared in the Los Angeles Times on Feb. 18, 1979. I kept the signed original manuscript. It is among my most treasured possessions. That and the memory of the meals we later shared in the years before his death in 1985.